Rolex DeepSea Challenger at Piccards Hubbard Medal in Washington

@ National Geographic Society’s “Evening of Exploration” in Washington DC on 14 June 2012.

Sections of the following text are taken from an official National Geographic press release.

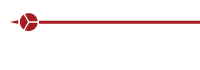

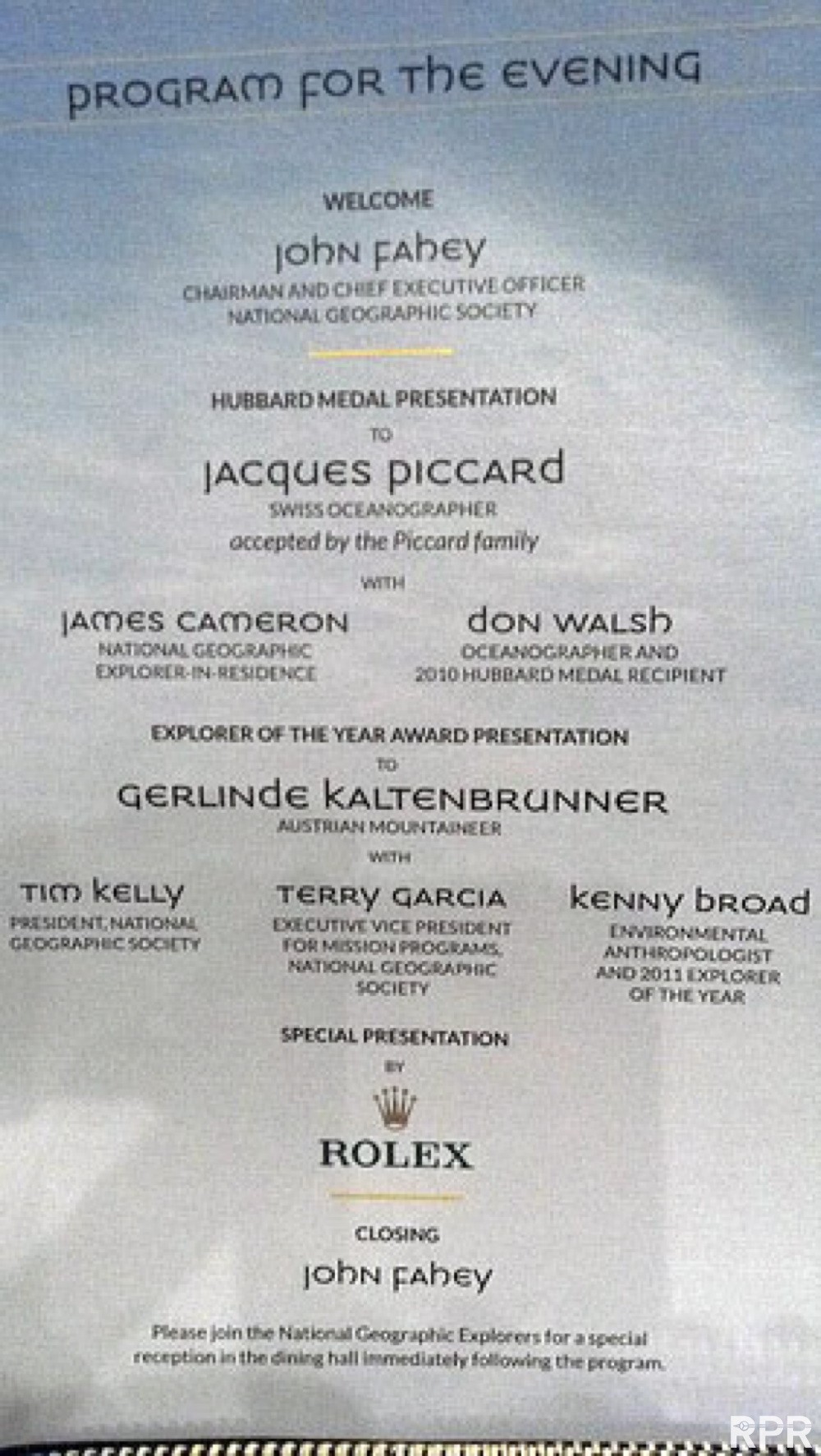

After four solid days of meetings and presentations surrounding the 2012 Explorers Symposium (and chronicled at #ExplorersWeek), more than 50 world-class explorers and many others from the National Geographic Society gathered last night for the “Evening of Exploration” presented by Rolex, to honor two particularly intrepid and inspiring explorers: the late Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard, and Austrian alpinist Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner.

Fifty-two years after he and U.S. Navy Capt. Don Walsh became the first people to descend nearly seven miles to the Mariana Trench, Jacques Piccard, who died in 2008 at the age of 86, posthumously received the National Geographic Society’s highest honor, the Hubbard Medal. Previous winners include Robert Peary, Sir Earnest Shackleton, Charles Lindbergh, the Apollo 11 astronauts, Jane Goodall, Robert Ballard, Don Walsh himself, and Jacques’ son Bertrand, who lead the first non-stop, around-the-world balloon flight.

Journeys to Earth’s topographic extremes were honored during last night’s “Evening of Exploration” at National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington, D.C. Ocean explorer Jacques Piccard posthumously received the Hubbard Medal – the Society’s highest honor – while mountaineer Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner was crowned Explorer of the Year.

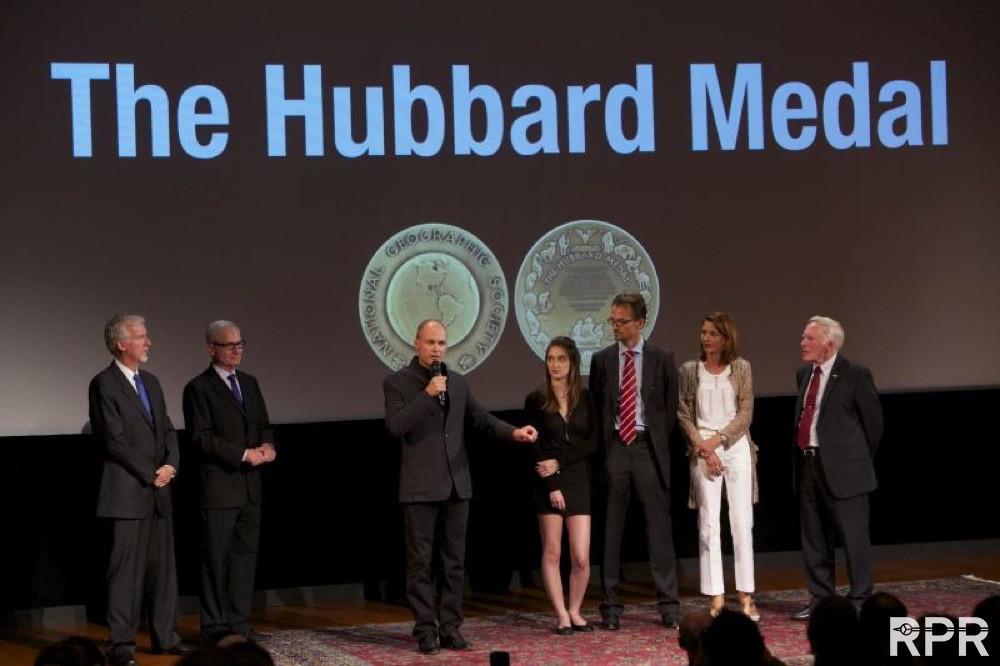

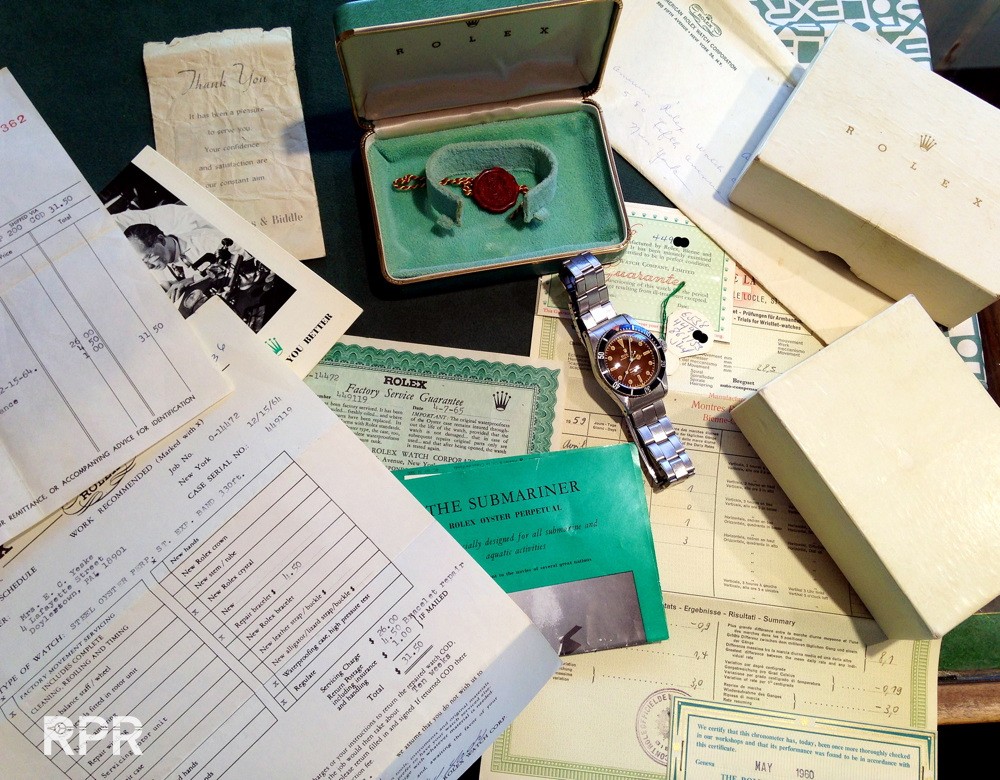

On January 23rd, 1960, Piccard was sealed inside the Navy’s Trieste bathyscaphe with Don Walsh, and the two men spent four and a half hours descending to the ocean’s deepest trench. They saw firsthand, in the form of a solitary, possibly very lost fish, that life in the ocean depths was possible, settling a question of much scientific debate. Piccard later described the experience: “Like a free balloon on a windless day, indifferent to the almost 200,000 tons of water pressing on the cabin from all sides, balanced to within an ounce or so on its wire guide rope, slowly, surely, in the name of science and humanity, the Trieste took possession of the abyss, the last extreme on our earth that remained to be conquered.” This exceptional historic Rolex event I already honored, together with Bertrand, with our limited Rolex Piccard Deepsea Edition in 2009.

Until earlier this year, Piccard and Walsh had been the only people to visit the Mariana Trench. It’s amazing to me that this milestone happened so long ago, and yet it still stands as one of exploration’s greatest accomplishments, even if that feat was more technical than physical. In this sense, the deep-diving expedition was similar to the Moon landing: a goalpost erected in the ‘60s, untouched for decades.

The Evening of Exploration capped off the National Geographic 2012 Explorers Symposium, a two-day conference where legions of explorers and scientists trek back to civilization to present their findings from the far reaches of the globe.

Inside the “Evening of Exploration”

The event kicked off with opening remarks by NG Chairman and CEO John Fahey, who was followed by Don Walsh and Explorer-in-Residence James Cameron. Before beginning their presentation of the Hubbard Medal to Jacques’ family, Cameron announced he had some other business to take care of first.

Explorer-in-Residence James Cameron (right) presents NG Chairman and CEO John Fahey (far left, with Don Walsh) with an official NGS flag he brought to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. Photo by Becky Hale/NGS

He then unfurled an official National Geographic Society flag, with its bands of brown, green, and blue representing the earth, sea, and sky which people have explored with support from the Society for nearly 125 years. Handing it over to John Fahey, he said he was honored to return this flag, which he had carried under his seat on board the submersible Deepsea Challenger when in March of this year he became the only other human being to visit the bottom of the Mariana Trench. Fahey accepted it and promised to find somewhere other than under his own seat to keep it.

The audience then watched as the lights dimmed and archival film and audio brought Piccard and Walsh’s 1960 dive back to life. While fifty years later Cameron would descend with cutting-edge film equipment, the original aquanauts on board Trieste had only their own eyes to record what they saw. Seeing this footage of the men and their sub at the surface, inside the sphere, and diving at shallower depths made it all the more clear just how far out and alone they were when they reached the bottom. An accomplishment which is hard to imagine because of its veil of depth and years became as riveting and heart-pounding as any adventure undertaken today (Watch a similar film about Trieste from Rolex).

Honoring a Pioneer

Cameron introduced Don Walsh saying that having been to the bottom of the ocean himself, he now has even more respect for what Walsh and Piccard did. All he had needed to do was follow in their path, he said, but “for them, there were no footprints in the snow.”

Jacques E. Piccard pictured in Palm Beach, Fla., several years after the descent which won him the Hubbard Medal last night. Photo by Otis Imboden/National Geographic

Walsh then shared more of the story of the original descent describing exploration as “curiosity put into action,” and presented the Hubbard Award with pride to “my Piccard family,” as he put it. Jacques’ son Bertrand then took to the stage with other family members, saying that some of his first and strongest memories are of hearing Don’s name, and of his father eagerly tearing open the packaging of National Geographic each time it arrived at their home (Read “Man’s Deepest Dive” by Jacques Piccard from the August, 1960 edition). He said that while there was an element of pure adventure to his father’s dive, there was also a major scientific aspect that would have an impact far bigger than the dive itself.

When Piccard and Walsh returned saying they had seen a fish swimming at the bottom of the ocean, it was interpreted as evidence that oxygen and other elements from the surface must circulate to the bottom, he said, and similarly that things from the bottom will someday make their way to the surface. At a time when governments were considering using the abyss as a dumping ground for nuclear waste, this was an important realization, and one that lead to the modern efforts to protect the ocean and all that’s in it.

Bertrand concluded by asking all in attendance to keep in mind that exploration shouldn’t just be for adventure, but that we “should explore the world to make it a better place.” Jacques E. Piccard pictured in Palm Beach, Fla., in the late 1960s. Piccard, who died in 2008, was posthumously awarded the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal. Image: Otis Imboden/National Geographic

Jacques Piccard

It was Jan. 23, 1960, when Piccard along with ocean explorer Don Walsh climbed aboard the Navy bathyscaphe Trieste and plunged to the floor of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench, the world’s deepest location, some 200 miles southwest of the island of Guam. Their destination was the trench’s lowest point, Challenger Deep, some 35,800 feet below the ocean surface. The only other individual to dive to this depth since then is filmmaker/explorer James Cameron, who reached Challenger Deep on March 26, 2012.

The Hubbard Medal will be presented to Piccard’s family by National Geographic Society chairman and CEO John Fahey, assisted by Don Walsh — who received the Hubbard Medal in 2010 — and James Cameron.

“Jacques Piccard was one of the first two pioneers to visit Earth’s deepest place,” said Fahey. “His accomplishment ranks alongside those of other Hubbard Medal recipients, like Charles Lindbergh, Louis and Mary Leakey, Jane Goodall and Robert Ballard. The passion and commitment of intrepid individuals like Piccard continue to inspire new generations of explorers.”

Piccard chronicled the dive for an article in the August 1960 issue of National Geographic magazine. He wrote: “Like a free balloon on a windless day, indifferent to the almost 200,000 tons of water pressing on the cabin from all sides, balanced to within an ounce or so on its wire guide rope, slowly, surely, in the name of science and humanity, the Trieste took possession of the abyss, the last extreme on our earth that remained to be conquered.”

Piccard and Walsh had to sit on small stools for the nine-hour trip down and back; they spent the hours keeping records of temperatures of water and the gasoline (used for buoyancy), amount of ballast released and water pressure. They kept in contact with the surface for most of the journey via a sonic telephone. When, after four-and-a-half hours, the bathyscaphe finally landed on the ocean bottom, Walsh and Piccard spied a fish, thereby answering a question about the presence of sea life in the deep that thousands of oceanographers had been asking for decades. By proving the existence of life where nobody expected it, the dive pushed governments to ban the dumping of toxic waste into the deepest trenches.

After that historic dive, Piccard went on to build four mid-depth submarines — called mesoscaphes — including the first tourist submersible, which took 33,000 passengers into the depths of Lake Geneva in 1964. He then built another mesoscaphe for Grumman and NASA to explore the Gulf Stream during a one-month drift mission in 1969.

Piccard, born in Brussels in 1922, studied in Switzerland and worked as a university economics teacher. He left teaching to help his father, Auguste (a physicist and the first man to take a balloon into the stratosphere), design the bathyscaphe, a submersible able to take humans to great depths below the ocean’s surface. It was in the bathyscaphe Trieste that Piccard and Walsh reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh emerge from the bathyscaphe Trieste following their successful descent to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench in January 1960. Piccard, who died in 2008, was posthumously awarded the Hubbard Medal on June 14, 2012. Photo by Thomas J. Abercrombie/National Geographic